Having looked at the structure and lexicon of Breton and Irish a bit, it is easy to see the relationship between these two celtic cousins. Considering that languages can only evolve so fast it is no surprise, even after centuries of separation, that historically related speech communities would still have some degree of linguistic kinship. What I find more interesting, though, is that despite several hundred years of separate social, political, and cultural development, Breton and Irish find themselves in very similar situations in the modern world, sharing many of the same challenges and difficulties. I believe this helps us to see that, circumstances aside, the plight of any minority language generally boils down to a few key social, political, and financial disadvantages and/or injustices.

As an Irish speaker, I feel an immense amount of empathy for and solidarity with the struggles of the Breton speaking community. I hear about different ways in which the use of Breton is condemned, judged, or mistrusted, and it sounds just like Irish speakers relaying their own experiences—so similar are the stories. I hear about the frustration felt by speakers of a language for which there is wide public support in theory, but very narrow support in terms of action or government intervention. The frustration is familiar as it seems to be a topic of conversation every time I turn on Raidió na Gaeltachta or read Tuairisc. Ultimately, what I am witnessing are the effects of the shared trauma of having the mother tongue stripped away from entire generations of speakers over and over again until the remaining generation of young native speakers is just barely holding on for survival.

history

In a seminar I attended in Quimper last summer, an interesting point was made about the first stages in the decline of Breton, and probably of any language. The beginning of the language’s decline was marked by the loss of the native language elite. That is, once the language was no longer spoken by the upper classes of society, the damage was probably irreversible and would only worsen.

Breton was the primary language spoken in Brittany, and it was even the language of the nobility up until the 12th century when political instability led to shifts in power and an increase in the use of French. Scholars say that once the language ceased to be spoken by the nobility and French gained political and economic clout, that constituted a tipping point for the Breton language, after which it would only see a steady decrease in numbers of speakers.

The same might be said of Irish, though the tipping point would have been reached a bit later in the 17th and 18th centuries. With the colonization of Ireland by England, Irish fell further and further into disuse in the eastern parts of the country around urban centers and seats of government. The Irish people came to see English as the only vehicle out of farming and poverty and thus equated it with “progress” and “the future”. Though many claim that the Irish language played an important role in the modernization of Ireland, the language shift had already begun and the point of no return may well have been reached long before the so-called “Great Famine” when devastating numbers of Irish-speakers were lost to both starvation and emigration.

The importance of the “native language elite” is very understandable in the contemporary context of language loss. Time and time again, we see that the educated gentry turn to dominant languages—languages of the colonizer—such as English, French, Spanish, Chinese, or Portuguese. Meanwhile the fate of smaller, more local languages rests on the shoulders of the disenfranchised, geographically isolated, and oppressed. Without currency among the elite, these languages become associated with the past, a lack of education, a lack of opportunity, and poverty. People begin to see their language as something that is holding them back.

The result of this for both Breton and Irish was that the languages became tied to smaller and more isolated communities, eventually falling out of use in the public realm in general. Breton and Irish were languages of the home or, at best, of the village, seldom used with outsiders unless sufficient trust or in-group rapport had been established.

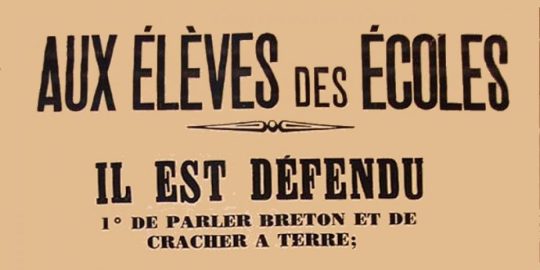

Such insularism was reinforced by the penalization, even criminalization, of both Breton and Irish by the French and British governments respectively. In British-occupied Ireland, Irish-speaking school children were often forced to wear a bata scoir around their necks. This was a wooden dowel or stick on which the schoolmaster would carve a notch every time the child was caught speaking Irish. At the end of the week the notches were tallied up and the child was punished, most likely beaten, that many times.

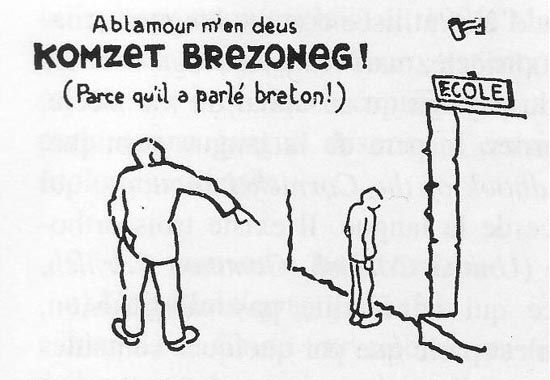

In Brittany, a similar technique was employed by the French, whereby a simple object such as an iron ring, tin can, or wooden shoe was deemed le symbole or la vache and was hung around a child’s neck as a humiliating punishment for speaking Breton in school. In a sinister twist, the only way a child could get rid of le symbole was to report another child for speaking Breton, and at the end of the day the child who was stuck with le symbole would be beaten or assigned manual labour. This naturally turned the children not only against their language but also against each other. Incidentally, this type of punishment remained in practice well into the 1940’s.

pathology

The younger generations had the language literally beaten and shamed out of them, and this is where the issue of trauma really begins. These two languages became associated with suffering, shame, judgement, inferiority, and servitude. The physical and psychological violence inflicted on entire generations of people in both countries is hardly ever acknowledged, much less processed or deconstructed by the subsequent generations, and as a result, there really does seem to be something pathological in the modern day relationships of Brittany and Ireland to their own languages.

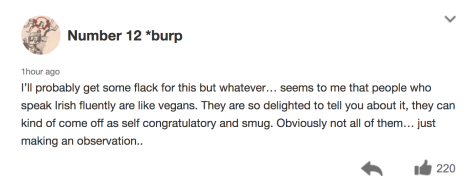

Part of the reason that Breton and Irish are not spoken more in the public realm is the amount of shame (or other dysfunctional emotions resulting from shame) tied to the languages themselves and then, ironically, to one’s own inability in speaking them. If you try to speak Irish to a stranger in Ireland, you can expect a range of resentful responses from an annoyed “Why don’t you just speak English?” to a defensive “Who do you think you are?” or even “You think you’re more Irish than me?” You might also find a few people willing to go along with it, but mostly people will just be annoyed.

In fact a recent tweet reveals just how much disdain people still endure for speaking Irish in public or even having Irish-language names. Again, this is intolerance by Irish people in Ireland for a language that is called…Irish.

In Brittany I was told of younger Breton speakers in the past complaining that they had a hard time using Breton with older speakers because the response was often: “I CAN speak French, you know. I’m not stupid.” In both cases, there is an incredible amount of linguistic dysfunction and insecurity in the presence of these languages. Ultimately this stems from the historic lack of value put on Breton or Irish and an ingrained notion that these languages are good-for-nothing dead-ends that only highlight one’s otherness rather than one’s place in a community.

I believe that these injuries constitute a community trauma, the effects of which are still present today. The communities have essentially been gaslighted into believing that the abandonment of their language was actually in their best interest. This applies just as easily to younger generations who grew up entirely without their language. They are still programmed to subconsciously believe that they are better off for having English or French as their first language. Programming like this fuels the “betrayal” mechanism of trauma, which allows the community to ignore the fact that they were wronged, much as an abused child blocks out the abuse of its caregiver for the sake of survival, as a coping mechanism. People often say “it’s a shame” that they don’t have the language of their grandparents, but they have been trained to believe that the dominance of English or French was ultimately for their own good. In an individual, this kind of thinking on a subconscious level keeps the trauma alive as it manifests in other areas of the psyche. One must wonder if something similar happens collectively on a community level. Does the trauma of previous generations with a language necessarily have an effect on the younger generations’ receptivity or inclination to learn it?

The trauma of language loss has not gone unnoticed by those working in the field of medicine in Brittany. Professor Jean Jacques Kress, from the faculty of medicine at the University of Brest writes:

Les grands parents parlent le breton, les parents sont bilingues et les enfants ne parlent que le français. En fait, la perte est intergénérationelle. Elle diffuse dans l’inconscient et est donc non brutale comme certains ont voulu le faire croire. On peut néanmoins, en se fondant sur l’observation psychiatrique, préciser de quelle nature est cette perte. On remarque en effet, nettement, une difficulté plus grande d’expression portant tout particulièrement sur l’affectif, les relations inter-humaines et la sensibilité individuelle. C’est ce que nous appelons l’alexithymie. Il n’est pas impossible, que cela soit une composante de la tendance à la dépression caractéristique des Bretons.

(The grandparents speak Breton, the parents are bilingual and the children only speak French. The loss is actually intergenerational. It diffuses into the unconscious and is therefore not violent as some would have you believe. Nevertheless, based on psychiatric observation, one can specify the nature of the loss. One can actually notice greater difficulty in expression in terms of emotions, human relations and individual sensitivity. This is what we call alexithymia. It is not impossible that this may be a factor in the tendency towards depression that is characteristic of the Breton people.)

And in fact, statistics show that Brittany has particular struggles with mental health. The rate of depression is measured at 20% above the national average and the rate of death by suicide is 65% higher than the national average.

Furthermore, substance abuse plays a role as well. Compared with the rest of France, there are 43% more alcoholism-related deaths before the age of 65, and Bretons are 80% more likely to experiment with heroin.

Marcel Texier, former president of Bretons du Monde (OBE), reflects on the link between these social problems and the loss of language:

De nombreux psychiatres ont établi une corrélation indiscutable entre la prévalence de l’alcoolisme et du suicide en Bretagne et la dévalorisation et la perte de la langue. Dieu merci, les choses sont en train de changer. J’en parlais, il y a quelques années, au Docteur Guy Caro, co-auteur d’un livre sur le sujet. “Le tableau est moins sombre qu’il y a quelques décennies”, m’a-t-il dit, “manifestement, dans la mesure où la langue bretonne, l’identité bretonne se portent mieux, l’alcoolisme régresse.”

(Many psychiatrists have established an indisputable correlation between the prevalence of alcoholism and suicide in Brittany and the devalorization and loss of the language. Thank god, things are changing. I was talking about it a few years ago with Dr. Guy Caro, co-author of a book on the subject. “The situation is less bleak than it was a few decades ago,” he told me, “clearly, as the Breton language and the Breton identity fare better, alcoholism decreases.”)

It is not surprising, that we can see similar phenomena in Ireland. A UNICEF study last year revealed that Ireland has one of the highest teen suicide rates in the European Union, yielding 10.3 suicide per 100,000 as compared with the national country average of 6.1. On top of that, nearly 40% of drinkers in Ireland typically binge while drinking, and for almost a quarter of them, this is a weekly occurrence. These problems are no doubt multi-factorial, but one cannot ignore that they can more or less be expected in communities that have had their language taken away.

One report by Hallett, Chandler, & Lalonde notes a significant correspondence between aboriginal language knowledge and lower youth suicide rates in First Nations communities of B.C., Canada. Ghil’ad Zuckermann and Michael Walsh go further in their paper on Barngala language revitalization in Australia and discuss language as central to a people’s well-being, drawing a relationship between language gain and increased mental health.

The outspoken Breton poet Xavier Grall touched on this theme in writing about his own experience outside of his language. Grall grew up in Paris but eventually renounced city life and moved back to Brittany to live off of the land and raise his family. He struggled immensely with not knowing the Breton language and wrote and debated extensively about its centrality to the Breton identity, albeit in French. He referred to the state of living outside of one’s own language as “cette atroce division mentale”—this agonizing mental division.

Nous sommes condamnés au dédoublement. Tous. D’abord, nous avons la malchance d’écrire dans la langue française. Nous avons cette tare de ne point connaître la langue de notre personnalité. Ensuite, nous vivons de la France qui fut, paraît-il, notre mère ! A Paris, ce dédoublement peut aller jusqu’à la folie. (…) Les équivoques sont constantes. La gueule double de Janus. Au risque de passer pour félon aux yeux des uns et des autres.

(It is our curse to have to live as divided beings — all of us. First because we must unfortunately write in the French language, since we suffer from the shameful affliction of not knowing the language of our own personality. Secondly, we make our living off France which was, so we are told, our mother! In Paris, this division of the self can lead to tragedy. It may drive some to madness, “the kind you lock up”, as Rimbaud said. One is constantly torn between two selves, like a two-headed Janus. With the risk of being taken for a traitor by everyone in the end.)

Grall, Mémoires de ronces (English translation by Gary German)

A teacher of mine recalled psychiatrists in Brittany in the 70’s telling him that at least 50% of their elderly patients were dealing with trauma due to language loss. This would have been the generation of Bretons who grew up in entirely Breton speaking environments only to see their language nearly vanish during the course of their lives. Philippe Carrère, psychiatrist and founder of the Société bretonne d’ethnopsychiatrie also touches on this loss and the collective implications thereof in his two volume work Ethnopsychiatrie en Bretagne.

If we can hone in on one general pathological theme as concerns the modern day rejection of Irish and Breton, it would have to be “shame”. There is the shame of having lost the language in the first place, a feeling felt by all generations. There is also the shame beaten into the older generations for having spoken an “inferior” or “backward” languages. And finally, there is the shame of the younger generations for not being able to speak their national language, often a raw nerve that is easily aggravated when confronted with the fact that these language do in fact still exist and can’t just be swept under the rug. Whichever variety, this shame is a destructive force on the psyche. It causes one to dissociate from the group to which they belong, and this ultimately contributes to fragmentation in society.

xenolects and totemization

Aside from the psychological problems related to intergenerational trauma that Breton and Irish share (along with countless other languages in similar situations), there exists a host of other parallel problems that mirror each other.

First of all, because both languages were relegated to home life and were only used as community languages in the most isolated areas, the differences between the various dialects were reinforced and perhaps even enhanced. Just as a Breton speaker from Bro Leon might hardly understand a Breton speaker from Bro Gwened, an Irish speaker from An Daingean will certainly have to pay more attention to understand someone from Tory Island. Differences in pronunciation, spelling, vocabulary, and to some extent grammar meant that once revitalization movements began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the leaders of these movements were met with the question of exactly which variety of the language they were promoting.

In the case of Irish, the three main dialect branches are not so divergent as to be irreconcilable, and an official standard, An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, was developed that incorporated characteristics of all three varieties. Breton, though, had a bigger challenge considering that the Gwened varieties of the language differ significantly from the other three dialect groups (Leoneg, Kernewek, and Tregereg). This resulted in two spelling standards: KLT for the latter dialects and another orthography (or more) for Gwenedeg.

In all instances, though, these standards, seen as necessary for the effective teaching and dissemination of the languages, have not always been well received by native speakers themselves. There are many stories of native Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht being perplexed by the Irish of Dubliners who had come to practice their language skills. These outsiders are often seen as speaking something very artificial and awkward sounding, hardly considered Irish at all by native speakers. Poet Cathal Ó Searcaigh speaks of Gaeilge mhaide na leabhar—wooden Irish from books—the way people in his Donegal Gaeltacht would refer to the non-native, standardized Irish that outsiders would speak when visiting.

Now that there are generations of children who have learned to speak fluent Irish through the Irish-medium Gaelscoil system, there is a considerable population of Irish speakers whose main dialect of Irish is this so-called artificial, wooden Irish. This variety of Irish lacks many of the phonological intricacies of Gaeltacht varieties of Irish and uses many English-influenced constructions and calques, yet also employs artificial-sounding, neologisms where native speakers from the Gaeltacht would generally just use an English word. The resulting language is often labelled a xenolect, a variety that on the surface resembles the original language but lacks many of the fundamental elements. Many native speakers of Irish claim that Gaelscoil Irish lacks the essence or spirit of Irish, some going so far as to say that the language would be better left to die out altogether. This creates a definitive rift between the communities of native speakers in the Gaeltacht and the often urban-based language enthusiasts who carry the language forward, albeit in an altered form.

Michael Hornsby very concisely sums up the phenomenon on his blog:

The situation is indeed complicated, and quite tense, as people who grew up speaking the language try to make sense of their position in relation to these ‘new’ speakers, whose presence can reinforce a sense of double alienation – firstly, from deep memories of actively being discouraged from using the language publicly and an associated sense of shame of being a minority language speaker; and secondly, by the appearance, in their later years, of younger speakers who say they are speaking the same language as them, but who sound markedly different from what they remember growing up. For new speakers, who are attempting to reconnect with their immediate heritage or who are symbolically resisting globalization through learning a local, non-majority language, this confusion on the part of older, native speakers can produce in them a sense of entrenchment or defensiveness.

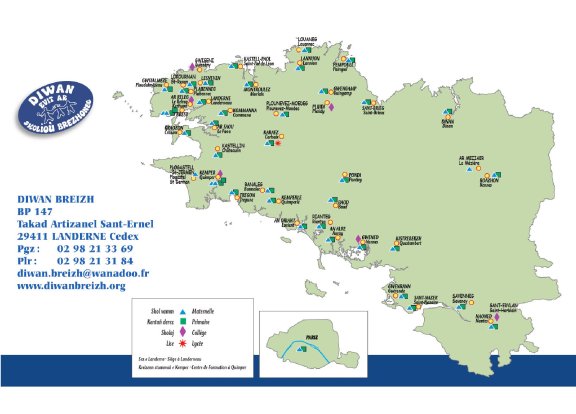

A similar xenolect situation has arisen in Brittany out of the Diwan schools, Breton-medium schools that have been growing in popularity since the late 1970’s. One of my Breton teachers cautioned us against the many imperfections and francismes used in Breton-speaking TV and radio programs, which are often presented by the progeny of the Diwan school system. The ever-present Daoust hag-eñ…? is an overused interrogative construction mirroring the French Est-ce que…? Another example is Bez ez eus…—there is—which is not technically incorrect but is overused in non-native Breton probably because it mirrors French word order more closely than the other possible sentence patterns for “there is”. Such constructions are often cumbersome to the native ear but they are common in Diwanek varieties of Breton which, for better or worse, seem to be here to stay.

Another modern day problem that revitalized languages often face is their own totemization. Revitalization movements often put a lot of focus on the visibility of the language. This may entail using the language in public and official signage (generally alongside a more dominant language), short utterances in the language to introduce important cultural or political speeches, the usage of isolated, sometimes untranslatable words from the revitalized language when speaking the dominant language, etc. And it is true that all of these instances increase the visibility of the language, but they usually do not do much for the actual state of the language itself. Bilingual road signage is ubiquitous in Brittany and Ireland, but this doesn’t change the fact that you can scarcely find the languages spoken in public anywhere.

Such signs are token nods to the existence of the language in question, but these gestures often do little more than give people a false sense of security and complacency. They can make a people feel that their language is more viable than it actually is, and, more to the point, that somebody else is taking care of it.

In fact, if we take into consideration the intergenerational shame that many are walking around with, these constant reminders of the existence of the language, coupled with the average person’s inactivity or lack of personal engagement with the language, may just perpetuate subconscious feelings of shame or resignation. By this, I by no means wish to say that surface gestures visibility towards revitalized languages are necessarily destructive, but rather that they must be supported by active engagement of the population to use and incorporate their language into their daily communication. Otherwise, their language will run the risk of totemization and its progress in the process of revitalization will be stunted.

political challenges

Totemization brings up another risk in that it can reduce the language to a superficial symbol that is widely recognized but seldom thought about or explored on a deeper level. This is exactly the kind of symbol that can be easily co-opted for political or other reasons and used to push an agenda that has nothing to do with the preservation of the language itself. Ultimately such exploits will deeply hurt the revitalization movement.

A prime example of this is the use of the Breton language and other cultural motifs in the Nazi-sympathizing Breton nationalist movement of the 30’s and 40’s. A portion of Breton nationalists saw the Nazi occupation as their way out of French occupation, and one publication that served as a platform for this sentiment was the militantly nationalistic Breiz Atao—Brittany Forever. The publication’s contributors were French-speaking, Breton intellectuals who co-opted the Breton language for the title of their publication but did nothing to actually promote it. The language was simply used as an empty symbol to promote otherwise unrelated ideologies. By the time the war was over, there had been enough use of the language and other cultural symbols to push the collaborationist, nationalistic agenda that it hurt the image of the Breton language and identity, and this most likely contributed in part to the increased speed of decline over the following decades.

This problem continues today. As I was researching this article, I discovered that there is now a website called Breiz Atao hosting mostly political content taking a very xenophobic, nationalistic stance on current issues. It appears to speak in the name of Brittany and the Breton language, but their content is little more than inflammatory scapegoating. It’s easy to rally behind a flag and language, but dedicating oneself to learning a language, particularly a very small, regional language, requires a certain amount of inner reflection and generally breeds acceptance and openness. I suspect Breiz Atao has no interest in such openness.

In Ireland, particularly in the north, the language simply cannot escape politics. While political agendas have motivated many to learn and use the language, as we are seeing today with the movement to demand an Irish Language Act, there are still those who associate the Irish language with nothing more than the Provisional IRA and dismiss its legitimacy entirely. In a recent editorial, Northern Irish protestant Richard Irvine reflects on the attitudes in his community towards the Irish language:

The Irish language, to me, and to the vast majority of my peers, was never a real language—rather, it was a treachery, a plot, and a Machiavellian political scheme of the disloyal and the dangerous.

And this is part of the reason that the government in Northern Ireland remains suspended. Petty fear is preventing the DUP from allowing itself to sign off on an Irish language act, despite the fact that Irish, particularly in West Belfast, is vibrant and far from being just a totem language. This stalemate illustrates a problem shared by Irish, Breton, and many other minority languages—that the powers that be find these languages to be such a threat to the status quo that they simply refuse to cede them any recognition whatsoever.

moving forward

What excites me the most when I look at the Breton and Irish revitalization movements nowadays, is the grassroots activism aimed at engaging people with their language and evoking an emotional response and connection to it. One of the major problems today is that people feel no ownership of their national languages, either because of linguistic inability or lack of exposure. The youth need to find a home in the language, and older native speakers need to warm up to the idea that languages change and the Irish and Breton of today won’t sound the same as they did 50 years ago.

In Brittany, groups like Ai ‘ta have succeeded in creating engaging, theatrical public actions, pop-up classes and other gatherings to give people a chance to interact with and show support for their language. For learners or Diwan speakers, it creates a welcoming context in which to use Breton outside of the classroom, and for native speakers it introduces the concept of taking pride in Breton and shedding some of the shame that has kept people from using it publicly.

In Northern Ireland An Dream Dearg has awakened considerable support for and engagement with the Irish language in the fight for an Irish language act, legislation protecting the language. People have taken to the streets to make their demands for linguistic rights and recognition known. Again, I think the importance here lies in taking the language out of the classroom and showing people, particularly young people, that it does have relevance to their lives and their identity and that they can take ownership of and responsibility for it. Without this ownership, the language is just another thing they are subjected to. Furthermore, without a sense of ownership over the language, people are not really able to recognize that something was stolen from them, and without acknowledging this, it is hard to heal the collective wound and linguistic shame of the community as a whole.

I think that there is an important lesson to be learned here. Speakers of minority languages anywhere in the world—not only Breton and Irish—need to feel that they are the caretakers of their language, like they have some command over its fate. If a generation of children is taught that their language is a lost cause, there isn’t much incentive for them to be invested in it. However, if the language is framed as something that they belong to and can take responsibility for, their instincts to take care of it will engage and their relationship to their own language will be marked by pride instead of shame.

Breton and Irish speakers would do well to look towards each other for inspiration and support. The battle of a minority language is at times a very lonely one, and given the connection and similarities between these two Celtic gems, I believe they could easily find strength in each other’s company.

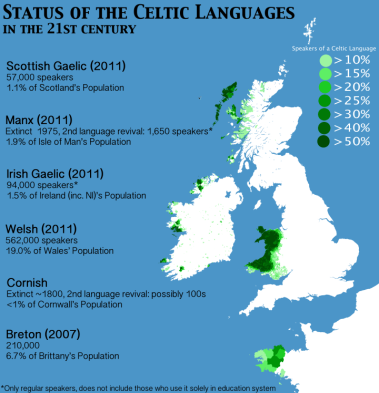

Wow, very enlightening! And I would’ve never guessed that Welsh is more common than Irish and even than Scottish.

LikeLike

‘agonising mental division’ is perfect. I grew up in the Brecon Beacons area of Wales and most of my friends growing up couldn’t speak anything but English, with a Welsh accent, bare-bones answers to GCSE questions and the odd word thrown into a sentence: ‘baban’ or ‘but’ being favourite.

When English friends came over, the immediate questions were ‘Why is all of your signage in Welsh if no-one even speaks it?’ and ‘How can you be Welsh if you can’t speak the language? Aren’t you just British?’ which is a dissertation in itself.

Nationality and language is such a hard question to unpick but labels like ‘totemism’ do help. Great comprehensive article!

LikeLike

Even English of the eternal Bard, Shakespeare, and Shelley, is being done to death . Removing the subjunctive, removing great poetry from curricula, removing the very concept of metaphor, dumbs down the entire transatlantic. I do not know how far that has gone in the Francophone world, worth checking. To rescue a language , then requires Poets, not some committee like Bertelsmann in Germany or the Academy in Paris. Poets must bring metaphor to the fore, and immediately!

LikeLike