In my last post I wrote about the presence of Yiddish in Brooklyn, but Yiddish is by no means the only Jewish language spoken here. So while we’re on the topic I’d like to talk a little bit about the phenomenon of Jewish languages in general, as well as a few that have found a home in this city.

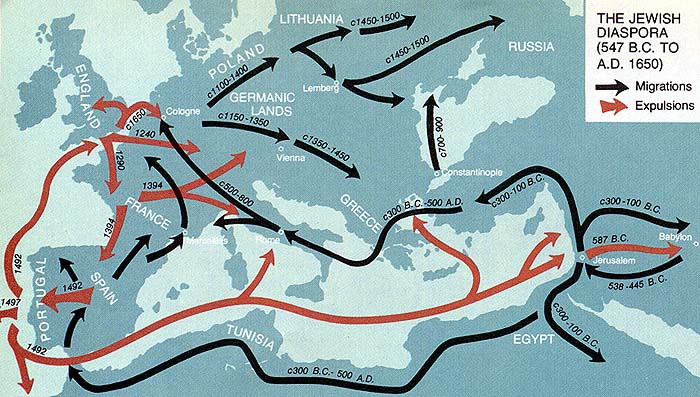

Let’s start with a little history first. Hebrew ceased to be the vernacular of the Jewish people around 200 BCE, first giving way to Aramaic and later to various other languages as Jewish communities spread throughout the world in diaspora. Here in New York, Yiddish is indeed the most well-known example of these diasporic languages. Jews in Germany around the 9th century spoke varieties of Middle High German but were literate in Hebrew and Aramaic, a source of many loanwords. As time progressed, many of these communities migrated to Eastern Europe. Over the centuries the variety of German that they continued to speak became heavily influenced by slavic languages, resulting in what we know today as modern Yiddish. But what about communities in other parts of the world? What did the Jews end up speaking in the Middle East, Spain, North Africa or even India?

The Jews from Spain spoke Judeo-Spanish (also know as Judezmo or Ladino). In North Africa and the Middle East, many spoke varieties of Judeo-Arabic and Jewish languages related to Persian. In India, one could find Judeo-Marathi and Judeo-Malayalam. Do you see the pattern here? Time and time again Jewish communities have adopted a language and modified it in certain ways while maintaining a distinct cultural identity, giving rise to a uniquely Jewish form of the original language. What is remarkable is how similar this process has been for so many Jewish languages throughout the world.

There are two characteristics that all Jewish languages share. First, all Jewish languages started out as already existing, non-Jewish languages, i.e. none of them developed from Hebrew or Aramaic. Second, these adopted languages took on Jewish characteristics in the form of loanwords and expressions from Hebrew and Aramaic. These borrowed vocabulary items tend to refer to concepts or items of religious importance, though Hebrew words or biblical expressions are often used in colloquial speech as well. (It should be noted that this phenomenon varies in degree, depending on the language.)

There is also a third characteristic shared by most, though not all, Jewish languages: the Hebrew alphabet. Languages, such as Yiddish, Ladino, varieties of Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Berber, Bukhari, and others were or are written in the Hebrew script, often modified to accommodate sounds not found in Hebrew. Judeo-Malayalam and Judeo-Marathi are not written in the Hebrew script, though many community members are able to read Hebrew for religious purposes.

Finally, another set of characteristics common to many Jewish languages, has to do with the mobile nature of diasporic life. Many languages that were adopted and reshaped by Jewish communities around the world were then taken on further migrations to new regions of the world. After the expulsion of Jews from Spain, Judeo-Spanish was taken to Morocco, Greece, Turkey, and the Balkans. Bukhari, a form of Judeo-Persian, was taken to areas of modern day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. This kind of movement often results in many archaisms being preserved in the Jewish language as it travels. The language crystalizes to a degree, maintaining vocabulary or grammar that eventually drops out of the original language. It also results in a tertiary language or set of languages that serve as a source for new borrowings, e.g. Judeo-Spanish that flourished in Turkey took on many Turkish loanwords. In all cases, the end product is multi-layered language, often exhibiting di- or triglossia, whereby each register may have a different language source that it draws from most. For instance, Ladino, the religious register of Judeo-Spanish is basically a word for word translation of Hebrew into Spanish-origin vocabulary, whereas secular writing is more throughly Spanish-based. Finally, in the colloquial register of everday speech, one finds an abundance of loan words from Turkish, Greek or other local languages, depending on where the community is located. Jewish languages have many ingredients.

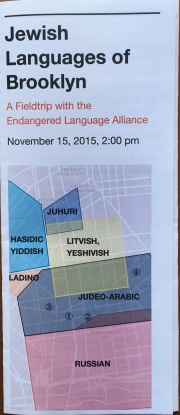

Now that some of these langauges have arrived in the U.S., they are transforming further and acquiring yet another layer due to borrowings from English. And this brings us to the event that inspired me to write this post in the first place. A couple of weeks ago the Endangered Language Alliance organised a Jewish languages walking tour in Brooklyn. The idea of the tour was to give some insight into the lesser-known Jewish languages in our city, and it featured members of communities that speak Syrian Judeo-Arabic and Juhuri. Needless to say, I was extremely excited.

of these langauges have arrived in the U.S., they are transforming further and acquiring yet another layer due to borrowings from English. And this brings us to the event that inspired me to write this post in the first place. A couple of weeks ago the Endangered Language Alliance organised a Jewish languages walking tour in Brooklyn. The idea of the tour was to give some insight into the lesser-known Jewish languages in our city, and it featured members of communities that speak Syrian Judeo-Arabic and Juhuri. Needless to say, I was extremely excited.

A young member of the Juhuri speaking community, Roza Shamailova, and her Juhuri teacher, Simon Mardakhayev, spoke to us first. Juhuri, sometimes referred to as Judeo-Tat, is a language spoken in Azerbaijan and Dagestan and now in Israel and the United States. It is most closely related to modern Persian, but still has characteristics of medieval Persian, borrowings from Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, Azeri, and Russian. It even exhibits the phonological phenomenon of vowel harmony, common to Turkic languages such as Azeri. Juhuri also has sounds not found in Persian to accommodate the traditional Mizrahi pronunciation of Het (ח) and Ayin (ע). Written Juhuri has undergone many changes, first having been written in the Hebrew alphabet, then a modified Roman alphabet in the 20’s, and finally the Cyrillic alphabet under the Soviet Union. You can find in Juhuri all the multi-layered characteristics of a typical Jewish language.

Juhuri has not been widely passed on to the younger generations in recent years and has less than 100,000 speakers worldwide. In Azerbaijan and Dagestan pressure to speak Russian and Azeri, as well as mass emigration, has reduced the usage of the language. In Israel and the U.S., pressure to speak Hebrew and English has done the same. In response to this, Roza and other young members of the Juhuri community in Brooklyn have organised classes to learn the language of their parents and grandparents. She said she has attained an intermediate level in the language and is motivated to continue learning, but it is certainly an uphill battle.

Before moving on with the tour, we were given a short Lezginka performance, a style of dance from the Caucasus popular with Juhuri speakers. The children who performed the dance were obviously proud and enthusiastic about their heritage, and I could imagine them taking an interest in learning Juhuri as they get older. Let’s hope the community’s efforts in teaching the language yield more resources and social relevance for Juhuri in years to come and that teachers like Simon (featured in the video above) continue to share their knowledge.

Our next stop on the tour was Bnei Yehouda, a small house synagogue within the Syrian Jewish community, led by Cantor Yohai Cohen. Cantor Cohen grew up in Israel with family from Syria and Tunisia, each speaking their own version of Judeo-Arabic. He said that the major difference that he notes between Judeo-Arabic languages and other varieties of Arabic is the use of Hebrew loanwords and expressions. If a person speaking Judeo-Syrian Arabic, for example, is careful to not use Hebrew-based words, their language could be mistaken for non-Jewish Syrian Arabic. He also commented that on Djerba island in Tunisia, where part of his family is from, the difference between Judeo-Arabic and non-Jewish Arabic often has more to do with how things are said and the choice of words, rather than the origins of the words themselves. This is where the debate between dialect and language comes in, as often happens with Jewish languages due to the nature of their development. Some will consider varieties of Judeo-Arabic just to be dialects of Arabic, not languages. Judeo-Arabic is distinct, though, in its use of the Hebrew alphabet, which has been employed in Judeo-Arabic literature throughout the Middle East and Northern Africa.

Cantor Cohen is also a master of the maqam musical tradition, a system of melodic scales, found in traditional Arab music. In Jewish communities this melodic system has been used for centuries to sing religious songs in both Hebrew and Arabic. This usage of maqams is as much a blending of different elements as Judeo-Arabic itself. Cantor Cohen takes great pride in the music and language, and the community is lucky to have him keeping both alive.

The tour continued on to Mansoura Bakery, run by a Moroccan French-speaker, whose family originally spoke Haketía, a variety of Judeo-Spanish. After loading up on sweets the tour continued to the final destination, Mizrahi Bookstore, housing a large collection of Sephardic/Mizrahi-focused books. I had other commitments and wasn’t able to make it to the bookstore (this time), but the tour left me with plenty to think about. How strong must a group’s cultural identity be to develop and maintain (across time and space) a language that is all their own? Certainly cultural isolation and the “otherness” imposed by outsiders play a role in strengthening a group’s hold on their language and identity as well, but I think the speakers’ sense of self is key.

It is amazing that Juhuri speakers’ ancestors spoke Hebrew, then Aramaic, then Persian, and were exposed to Arabic and Azeri and Russian, and today’s speakers still carry all of those layers on their tongues. It should only make sense that the language would continue to morph and add more layers as it moves to different parts of the world. But a very strong cultural identity and real conviction is going to be necessary to give Juhuri (and most of these other languages) any place in contemporary New York City, let alone in the future. Minority languages are not spoken out of need or convenience in today’s world, but rather because of the sense of belonging and history that they provide. I think that as more people realise this, we’ll come closer to preserving and cultivating the linguistic richness that still exists around us today.

Wow! That is so cool! Did they say anything about Jewish Aramaic in NYC? I know there are a lot of dialects left in Israel–mostly among old folks. I was hoping some might have been preserved in NYC.

LikeLike

thanks for reading! i haven’t heard of any judeo-aramaic dialects spoken in new york, at least on a community level, but i wouldn’t be surprised if there are pockets here and there. something to look further into!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could Papiamento be considered a ¨Jewish language¨, since Ladino did form the basis for it. Native American (Lokono), West African (Still disputed), Iberian (Por & Spa) and Italian also greatly influenced it.

LikeLike

bo por papia papiamentu?!

it’s an interesting point. i don’t think it would quite fit the bill as a “jewish language” because jews would be a minority of papiamento speakers, not the main community holding the language, and there is no hebrew/aramaic vocabulary element to the language either. i’m curious about the ladino/judeo-spanish pieces of papiamento’s origins though. i’ll be in curaçao in january and was hoping to see if anyone at the mikvé israel-emanuel synagogue would have any insights or information. keep an eye out for my papiamento post in january!

LikeLike